What Colored Tattoo Inks Contain Nickel

- Research

- Open Access

- Published:

Distribution of nickel and chromium containing particles from tattoo needle wear in humans and its possible touch on allergic reactions

Particle and Fibre Toxicology volume sixteen, Article number:33 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Allergic reactions to tattoos are among the almost common side furnishings occurring with this permanent deposition of pigments into the dermal skin layer. The characterization of such pigments and their distribution has been investigated in contempo decades. The health touch on of tattoo equipment on the all-encompassing number of people with inked peel has been the focus of neither research nor medical diagnostics. Although tattoo needles contain high amounts of sensitizing elements similar nickel (Ni) and chromium (Cr), their influence on metal deposition in skin has never been investigated.

Results

Hither, we report the deposition of nano- and micrometer sized tattoo needle wear particles in human skin that translocate to lymph nodes. Usually tattoo needles contain nickel (half-dozen–8%) and chromium (15–twenty%) both of which prompt a high charge per unit of sensitization in the general population. As verified in pig skin, wear significantly increased upon tattooing with the suspected abrasive titanium dioxide white when compared to carbon black pigment. Additionally, scanning electron microscopy of the tattoo needle revealed a high wear after tattooing with ink containing titanium dioxide. The investigation of a pare biopsy obtained from a nickel sensitized patient with type IV allergy toward a tattoo showed both wear particles and iron pigments contaminated with nickel.

Determination

Previously, the virtually inevitable nickel contamination of iron pigments was suspected to be responsible for nickel-driven tattoo allergies. The evidence from our study conspicuously points to an boosted entry of nickel to both skin and lymph nodes originating from tattoo needle wear with an every bit yet to exist assessed impact on tattoo allergy formation and systemic sensitization.

Background

Delayed type Iv allergies triggered past tattoos institute the 2d most reported side furnishings referred in the literature [1] and, eastward.thou., account for 37% of all patients in a Danish tattoo clinic [2]. Combined with the prevalence of tattooed individuals—ranging from 8.5 to 24% of the population across Europe and the Us [iii]—this shows that a tremendous number of people are affected. By case reports identify chromium (Cr) [4], mercury (Hg) [v], cobalt (Co) [half-dozen] and nickel (Ni) [7] as sources of chemical element-related allergies triggered by tattoos. Cleavage of organic pigments past UV or light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation irradiation displays another source of carcinogens or sensitizers [8]. Analyses of tattoo inks frequently reveal a variety of carcinogenic and sensitizing elemental impurities such as Ni, Cr, Co or Hg that are mostly introduced by pigment particles [nine]. Information technology has also been occasionally speculated that metal exposure might derive from the tattoo needle used to implant the tattoo paint into the skin [10].

Tattoo pigments including impurities are transported to the draining lymph nodes and likely to other organs either passively or by agile transport through phagocytizing cells [11, 12]. In the lymph node, presentation of allergens to immune cells might result in sensitization. Mobility and kinetics of pigments including such sensitizers are highly dependent on particle size. In a previous study on the biokinetics of tattoo pigments in homo tissue samples nosotros found indications of preferred transport of smaller particles of an organic pigment from the pare to regional lymph nodes [13]. The average particle size in tattoo inks may vary from < 100 nm to > 1 μm [9, 14, 15]. The increased adventure of nano- compared to micro-sized particles is due to their increased surface-to-volume ratio, which consequently leads to a potentially college release of toxic elements, if present. Additionally, nanoparticles in general can directly enter cells [16]. Smaller particles are more easily distributed, but may also be more than easily excreted from the trunk [17]. All the same, little data exist on tattoo pigment sizes in different human tissues.

In this written report, synchrotron-based nano-X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was used to analyze human skin and respective draining lymph nodes with the aim to establish a database of pigment particle sizes and elemental contaminants deposited in the man body. Data from the skin and lymph nodes of five donors with no known tattoo-related health effects were analyzed and compared to a pare biopsy of a patient with a blazon IV tattoo allergy and confirmed Ni sensitivity. Partly metallic characteristics of Ni and Cr in fe (Fe) particles were identified by ways of synchrotron nano X-ray absorption nearly-edge structure (XANES) in the tissue specimen, which led us to investigate steel wear from tattoo needles and its subsequent quantification using postmortem tattooed pig pare.

Results

Nano- and micrometer sized metal particles in skin and lymph nodes

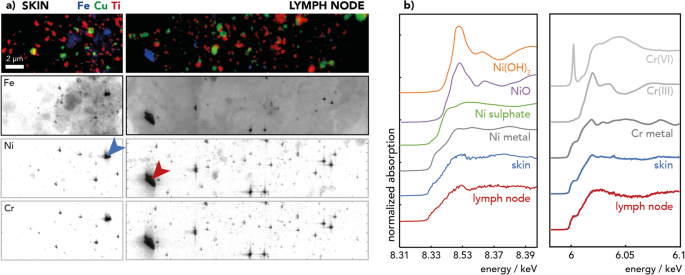

Tattoo particles in human peel and lymph node sections from deceased donors were analyzed by means of synchrotron nano-XRF to make up one's mind the particle size and elemental composition (Fig. 1a, Tabular array 1, Boosted file 1: Figure S1). Samples were selected with a special focus on bright colors, such as green, blue, and cherry, to obtain samples in which use of organic pigments mixed with inorganic white titanium dioxide (TiOtwo) was presumed. All exogenous elements detected in the skin announced to be transported to the corresponding draining lymph nodes, without significant modification of their size. Particle sizes ranged from 50 nm or smaller (resolution limit) up to a micrometer and depended on the particles elemental composition.

Synchrotron nano-X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and nano- 10-ray assimilation near-edge structure (XANES) analysis of representative skin and lymph node sections. a XRF elemental maps of donor 1 of titanium (Ti) from titanium dioxide, copper (Cu) from copper phthalocyanine, fe (Fe), chromium (Cr) and nickel (Ni) from steel debris, caused at beamline ID16B with a resolution of 50 nm. Arrows point the regions where XANES spectra were caused. b Cr and Ni K-border XANES spectra of pare and lymph node samples mainly bear witness metal Ni and a mixture of metal Cr(0) and ionic Cr (Iii) when compared to reference spectra

Ti particles found in all tattooed samples derive from TiO2 (mixture of anatase and rutile crystal structures) as revealed by XANES analysis (Additional file 1: Table S1). TiO2 particles were more often than not uniform in shape and size, ranging from approximately 200–300 nm in well-nigh samples (Table one).

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) analysis revealed the presence of organic copper (Cu) phthalocyanines pigments, amid others (Additional file 1: Table S2). Presence of Cu is further verified past XRF analysis (Fig. 1a), which resolved Cu-phthalocyanine pigments with sizes of nearly 100 nm equally well every bit big agglomerates in the micrometer range (Table 1, Additional file 1: Effigy S1).

In all five skin and four lymph node samples of 3 donors analyzed via nano-XRF, Fe-Cr-Ni particles were observed in shut relation to Ti particles (Fig. one, Additional file ane: Figure S1). Their size varied from resolution limit of 1 pixel, which corresponds to 50 nm or smaller, up to the micrometer range. Hence, micrometer-sized particles also reach the lymph nodes. The chemic speciation of both Cr and Ni in these Iron particles was a mixture of metal and oxidized elements as revealed by the XANES analysis (Fig. 1b, Additional file i: Tables S3 and S4). Therefore, Fe particles more likely originate from steel particles than from Iron oxide pigments. Information technology must exist noted that the Ni concentration assessed by inductively coupled plasma (ICP)-MS was below the limit of detection in six out of 13 samples of tattooed donors and were only noticeably increased in iii samples when compared to the controls (Additional file 1: Table S5). In contrast, synchrotron nano-XRF, with its very high sensitivity and high spatial resolution capability, can reveal loftier concentrations of small particles present in a restricted area of the skin. More specifically, information technology showed that all tissues exposed to tattoo pigments contained Fe-Cr-Ni steel particles.

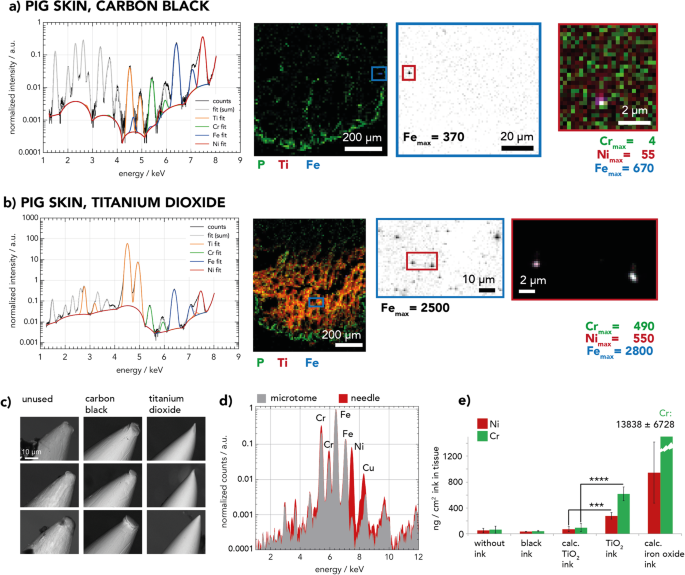

Steel particles are being abraded from the tattoo needle by TiO2

The steel debris found in human tissues aslope tattoos in the nano-XRF analysis may potentially derive from three sources: contaminated inks, contagion during sample grooming (clothing from the microtome blades used for tissue sectioning), or habiliment from tattoo needles. Nosotros analyzed 50 tattoo inks from worldwide origins by ways of nano-XRF that were either black, white or red and partially contained TiO2. None of the inks independent metallic Fe particles along with Ni and Cr contagion as the ones discovered in the skin and lymph node samples (data not presented). Furthermore, the microtome blades did not contain Ni, which excluded contamination from sample preparation (Fig. ii, Additional file i: Table S6). Yet, all 12 tattoo needles analyzed contained 15–twenty% Cr and 6–9% Ni (Fig. 2nd, Additional file 1: Table S6). To further determine the steel droppings' origin, we tattooed grunter pare with either carbon black ink or TiOii ink, with the latter known to have abrasive properties (Fig. 2). Both inks were assessed beforehand and were found not to contain steel particles (Boosted file 1: Figure S2). The results show that the squealer skin tattooed with TiO2 ink (Fig. 2b) contained past far more Iron-Cr-Ni particles than the skin tissue tattooed with carbon black (Fig. 2a).

Nano-X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses of pig peel tattooed with carbon black or titanium dioxide (TiO2) inks. a, b Zoom-in nano-XRF maps of tattooed grunter peel sections recorded at beamline ID21 prove a college deposition of iron-chromium-nickel (Fe-Cr-Ni) particles with white TiO2 ink (b) than with carbon blackness (a). Maximal (max.) intensities of elements are given for each element. c SEM images of 9 tattoo needles unused and later on tattooing of pig peel with carbon black and TiOtwo ink. Polished needle surfaces announced only after tattooing with TiO2 ink. d Table-top XRF spectra of tattoo needle and microtome knife. e Quantity of Ni and Cr per weight of tissue in grunter skin subsequently tattooing with carbon blackness, TiO2 or without (west/o) ink, analyzed past inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and estimated calc. TiOii ink (see text for explanations). Worst case concentrations of highly contaminated brownish fe oxide ink [9] were calculated in the same mode (calc. iron oxide ink). Asterisks indicate significances as identified by a two-manner ANOVA with a Tukeys multiple comparison test using all tattooed samples and calc. TiO2 ink. Pregnant differences of pig pare tattooed with TiO2 ink compared to calc. TiOtwo ink are displayed (*** =p < 0.001; **** =p < 0.0001). Data are displayed as mean of iii distinct samples ± SD. Abbreviations: P = phosphorus

Complementary scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the tattoo needle prior or subsequently use furthermore revealed a completely polished needle later on tattooing a skin surface equally footling as 2–iii cm2 with TiOii ink (Fig. 2c). Nano-XRF and SEM analyses evidence like metallic wearable induced past TiO2 when tattooing pig pare with rotary and gyre tattoo machines and corresponding needle equipment. The Ni and Cr deposition of steel particles was quantified by ICP-MS (Fig. 2e). The TiO2 ink showed minimal Ni and Cr background levels. The Ti counts per cm2 skin (tattooed with TiOtwo ink) were compared to those of a known amount TiOii ink to extrapolate the amount of ink in the peel (see Boosted file 1: Figure S3). Ni and Cr concentrations in untreated skin and in TiO2 ink were then used to calculate the expected concentrations of these elements in TiO2 ink tattooed pig skin (see 'calc. TiO2 ink' in Fig. 2e). Both, concentrations of Ni and Cr were significantly higher upon tattooing (see TiOtwo ink) compared to the calculated values. The additional elemental load deriving from abraded steel particles was calculated by subtracting the expected element levels (calc. TiO2 ink) from the mean quantified levels in tattooed squealer skin (TiO2 ink) which were 206 ng/cm2 and 522 ng/cm2 for Ni and Cr, respectively (Boosted file 1: Figure S3b). Withal, the boosted Ni and Cr concentration inserted into skin past this steel vesture particles is lower compared to the estimated deposition of these elements in skin upon usage of a highly contaminated brown ink (cf. calc. Iron oxide ink, Fig. 2e).

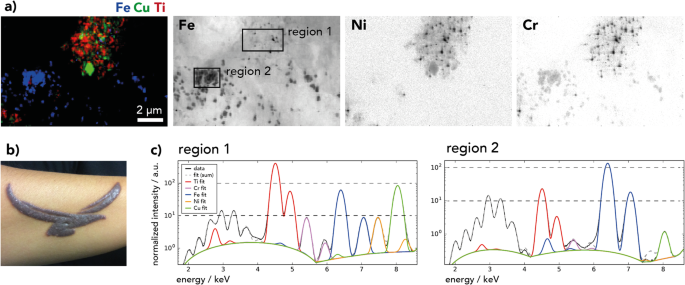

2 types of Fe particles are present in allergic pare reaction

We as well investigated the peel section of a patient who had experienced an allergic reaction to his tattoo (Fig. iii) and, as revealed by patch testing, was sensitized against Ni but not Cr. T-prison cell infiltration was verified by immunohistochemistry (Additional file 1: Figure S4). Organic pigment analysis by MALDI-MS revealed the presence of blueish Cu-phthalocyanine which, as mentioned in a higher place, tin be localized through high-resolution Cu nano-XRF maps (Fig. 3a, Boosted file ane: Table S2).

Allergic reaction to a red-brown tattoo of a patient sensitized to nickel. a Skin section nano-X-ray fluorescence (XRF) image recorded at beamline ID16B with singled-out areas of fe (Iron) pigments (region ii) and smaller Atomic number 26-chromium-nickel (Fe-Cr-Ni) particles (region 1) in titanium (Ti)-rich regions. b Photography of the skin'southward reaction to the tattoo before removal past dermabrasion. c Normalized XRF spectra in Fe pixels extracted from regions 1 and two, as indicated in the Iron XRF paradigm in (a). Abbreviations: Cu = copper

In region 1, Ti and Cu are present as large particles and are likely part of a blue ink. Fe particles are much smaller and contain Ni and Cr (Fig. 3c, Tabular array 1).

Region ii presents a loftier concentration and more than uniform distribution of Fe particles, only without Cu and Ti. The intensity of Cr is lower compared to region 1 and Ni is hardly detectable. Iron distribution is comparable to the one observed on nano-XRF maps of red atomic number 26 oxide tattoo inks (Boosted file 1: Figure S2). Therefore, Fe probable originates from blood-red-dark-brown Fe oxide pigments with a size of nearly 300–450 nm. The presence of a true Atomic number 26 oxide pigment as a color-giving ingredient is supported by the high Iron concentration quantified by means of ICP-MS in the allergic skin sample (Additional file 1: Tabular array S5).

In summary, the patient was tattooed with a cocky-mixed color deriving from ii inks, which likely resulted in differing ink particle regions in the peel. The particular presence of Fe-Cr-Ni particles in the Ti rich regions can be assigned to putative steel vesture particles from the tattoo needle (cf. Fig. four). Hence, the peel of this patient contains two kinds of potential Ni sources – steel vesture particles with high Ni concentrations and Fe oxide pigments with lower concentrations of Ni.

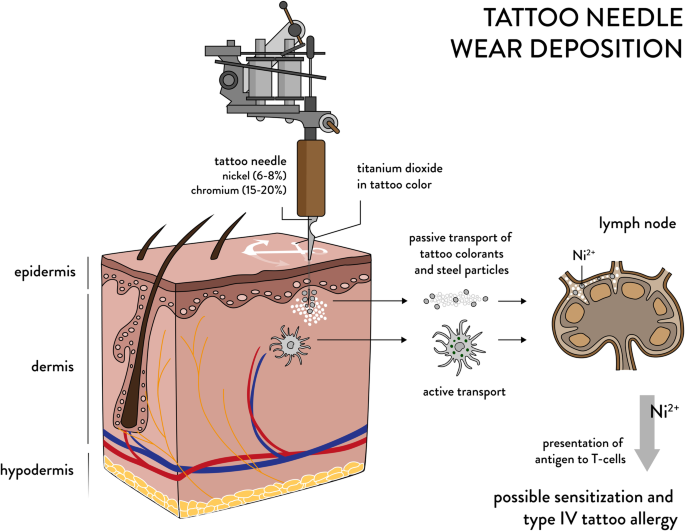

Tattoo needle article of clothing biodistribution and supposed contribution to allergy germination. Nickel and chromium containing wear particles are abraded past titanium dioxide containing inks. The steel used to manufacture tattoo needles contains half dozen-eight% nickel and 15-20% chromium. Pigments and wear particles are inserted into the dermal office of the skin. Both are passively and actively transported to the draining lymph nodes where Ni2+ ions as sensitizing species of nickel can be released. Antigen presentation to T-cells takes place in the lymph nodes as role of the adaptive immune response which is an obligatory process for sensitization and thus type Four allergy formation in the skin

Discussion

Our findings show that nano- and micrometer sized particles are abraded from tattoo needles when using TiOtwo-containing ink. These particles contain Ni and Cr and are permanently deposited in tattooed skin and are translocated to lymph nodes. Although the overall sample size was limited past the availability of specimens and the synchrotron beamtime, information technology is beyond doubt that the metal particles derive from the tattoo needle as result of pure mechanical stress. The particle degradation was additionally proven in pig skin and appeared only significant upon usage of TiO2 white ink but not with carbon black ink.

We also demonstrate that tattoo-derived particles larger than 2 μm are being translocated to the lymph nodes. We thus assume that a size threshold for particles transported toward the lymph nodes does not exist for the boilerplate tattoo particles of sizes below 100 nm to near 1 μm [14]. Since most of these wear particles are comparably modest and reach down to the limit of resolution of 50 nm, biodistribution to other organs tin be expected which is already known from human and animal studies [17, 18]. This study therefore provides the first proof that non just tattoo pigments but as well abraded Fe-Cr-Ni steel particles are distributed toward the lymph nodes [thirteen, 17, 19].

The tattoo reaction investigated in this article is classified as allergic type reaction. Tattoo allergies are characterized by non-infectious, chronic reactions with persistent reactions exceeding 3 months together with itching, swelling and dermal inflammation confined to one specific colour within the tattoo [20]. All these criteria were fulfilled with this patient.

Until now, the source of Ni and Cr in metal-related tattoo allergies was idea to exist primarily contaminated Fe oxide paint which commonly contains Ni, Cr, Cu or Co, amongst other elements [9]. Withal, nosotros analyzed peel tissue from a patient who suffered from a tattoo-related allergic reaction and constitute both Fe oxide pigments too as abraded steel particles in the inflamed skin. As the patient was sensitized to Ni, Ni allergy has likely caused the visible tattoo reaction.

Blazon Iv Ni contact allergy is triggered by the Ni2+ ion in humans [21]. The Niii+ ion may be released from the abraded steel particles through chemic amending by reactive oxygen species inside the phagolysosomes of cells [22]. Hence, like to Ni2+ release from steel implants or jewelry, the steel wear particles deriving from the tattoo needle can be sources of Ni2+ ion release [23,24,25]. Given the small-scale size and hence larger surface-to-volume ratio of the wear particles, a comparably higher Ni2+ release is expected, which may then lead to sensitization and allergic reactions in the skin [23]. Similar to tattoo allergies, the number of metal allergy-related implant complications from abraded steel particles is low in comparison to the prevalence of cutaneous metal sensitization rates towards Ni in the general population [26, 27]. On the contrary, people with failed implants take a two to iii times higher incidence of sensitization against metals. Thus, not every sensitized person will show a reaction to dermal depositions of these elements simply nevertheless may be more likely to develop an adverse reaction.

With the evidence provided in this study arises the question of whether metallic wear from tattoo needles may indeed, just as Fe oxide pigments, play a role in allergic tattoo reactions. A connection between adverse tattoo furnishings, implant failure and also the use of TiO2 in tattoo inks has already been reported [28, 29]. Sensitization is also promoted past co-stimulating factors similar inflammation, which may develop straight after tattooing due to the skin injury acquired by the tattooing process or if infections occur simultaneously [30]. The bear on of abraded particles from the tattoo needle and their potential function in metallic-related tattoo skin allergies is withal unknown. Farther investigations addressing a nickel sensitized cohort displaying tattoo allergy with and without tattoo needle vesture due to TiO2 inks compared to allergies driven past iron oxide pigments alone will be, notwithstanding, express by the availability of such samples.

Conclusion

In summary, the fact that all paint and wear particles are deposited in lymph nodes calls for special attention to be placed on allergy development. Since the underlying substances causing tattoo allergies are barely known, tattoo needle wear containing chromium and nickel found in this investigation brings up a new source of sensitizers that demand to be considered equally additional source in allergy development. To date, neither boosted nano-related effects nor a potential health touch of the utilized tattoo equipment are being considered in whatsoever tattoo legislation.

Methods

Human samples

Samples of tattooed skin areas and regional lymph nodes of five donors equally well as skin and lymph node samples of 2 additional donors without whatsoever tattoos were taken postmortem at the Establish of Forensic Medicine at the Ludwig-Maximilians Academy of Munich (court-ordered autopsies with no additional cosmetic impairment to the skin). The experiments were performed according to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. All samples were obtained anonymously without information on the donors' disease condition, causes of death or demographics. Hence, occupational or environmental exposure with loftier exposure with stainless steel or metal particles is unknown. We selected specimens with tattoos other than black which are more probable to contain TiO2 and organic pigments.

The shave biopsy of the allergic patient was taken upon informed consent due to medical indication. The patient was tattooed with a self-made mixture of black and red ink in one session to achieve a brown color in 2014. The patient experienced immediate discomfort with additional swelling and itching with some filibuster of several weeks. Later on a year, the patient sought medical advice. The prescribed betamethasone cream applied twice a twenty-four hours merely improved itching not swelling. The tattoo was removed in 2016. Tissue culture of removed skin was negative for mycobacteria. The patient showed a Ni (+++) patch test issue with no reaction toward Cr in 2016. Removed tissue was received upon informed consent. Tissue samples were stored in plastic bags at − 20 °C directly after excision and further processed for analysis within a year. Subsamples were cut using a standard scalpel and frozen in TissueTek O.C.T. matrix (Sakura Finetek, Staufen, Germany) for cryo-microtome sectioning. Sections for XRF analyses at ID16B and ID21 were performed on 12–xiv μm sections between two four μm Ultralene window films (Spex Sample Prep, Metuchen, NJ, USA). Sections were inactivated using a 4% formaldehyde buffer for x min and subsequently done with deionized water (twice, two–5 min) before being dried at room temperature.

Tattooed squealer pare samples

Abdominal sus scrofa skin was taken postmortem and stored at − 20 °C after hair was removed using an electric razor. Thawed skin was tattooed with a Cheyenne Hawk Thunder rotary tattoo machine (MT.Derm, Berlin, Germany) with diverse tattoo needles (cf. Additional file 1: Table S6) until an even color shade was achieved. Alternatively, a no-name coil tattoo auto was used. Tattooed specimens were prepared for microtome sectioning for XRF analysis as stated above. For ICP-MS analysis, skin pieces were cutting out with a ceramic knife. Side lengths were measured and used to calculate the surface areas of the dissected skin squares.

Synchrotron XRF

XRF analyses were carried out at the beamlines ID21 (micro-XRF) and ID16B (nano-XRF) at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, every bit previously described [31, 32]. For details encounter Boosted file ane.

XRF of microtome blades and tattoo needles

XRF analysis of 12 tattoo needles and 4 microtome knifes was carried out with a desktop Fischerscope X-ray XDV-SDD (Helmut Fischer GmbH Institut für Elektronik und Messtechnik, Sindelfingen, Frg). The instrument was equipped with an SDD detector with a 50 mm2 effective detector expanse and an aperture of iii mm in bore. The micro focus tube with tungsten target and glucinium window was set to 50 kV with a Ø 0.2 mm collimator. Each microtome knife also as each tattoo needle was measured at iv dissimilar positions for 30 s. For the microtome knife: two positions on the knife, two positions on the majority; for the tattoo needle: 2 positions on the tips of the needles, ii positions on the shaft of the needle.

SEM analysis

SEM pictures of tattoo needle tips were recorded with a TM3030 tabletop microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at 15 kV accelerating voltage. Command needles were analyzed directly out of the package. Needles used for tattooing with either black or TiO2 ink were cleaned with isopropanol in an ultrasonic water bath (Sonorex digitec, Bandelin Electronic, Berlin, Frg) to remove residual tattoo ink.

ICP-MS

For human tissue samples element analysis using ICP-MS was carried out as previously described [13]. For quantification of stainless steel vesture, the method was contradistinct to completely deliquesce the steel particles. Therefore, 50–150 mg samples were digested with half dozen ml HNO3 and two ml HCl in polytetrafluoroethylene vessels in a First 1500 microwave (MLS GmbH, Leutkirch, Federal republic of germany). Samples were treated with grand West for x min at a temperature of 210 °C inside the reference vessel and 100 °C exterior the protective beat out. Afterwards, the temperature of the shell was raised to 150 °C for an additional 15 min. A cool-down time of 40 min was programmed. Full microwave digestion of steel wear was successfully tested by decision of the recovery from stainless steel nanoparticles (AISI 304 alloy, Fe/Cr18/Ni10, 45 μm from Goodfellow, Huntingdon, United kingdom).

Samples were filled to 50 ml and subsequently analyzed with an iCAP Qc (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, U.s.) with 10 sweeps per sample, a resolution of 0.i u and a dwell fourth dimension of 0.01 s in − 3 Five kinetic energy discrimination way. 103Rh was used every bit internal standard. 52Cr and threescoreNi were monitored for quantitation. 49Ti counts were used to summate relative ink concentrations in different samples. Limit of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) were determined using the calibration curve method (DIN 32645). For Ni, 0.14 ppb was determined as LOD and 0.35 ppb as LOQ. LOD and LOQ for Cr were 0.08 ppb and 0.215 ppb, respectively.

MALDI-MS

Organic pigments in the tissue samples have been identified using MALDI-MS as previously described [thirteen]. Identification of pigments is based on the comparison of spectra to those of known pigment standards and must show corresponding molecular mass ions and other characteristic peaks.

XANES analysis

Athena Demeter software [33] was used for XANES spectra fitting to standard substances. Where necessary, multiple spectra were averaged and normalized within the PyMCA software [34]. Spectra were normalized in second guild aligned to a standard spectrum, earlier using linear combination fitting. Fitting of all combinations was carried out with a maximum of iv standards, all weighted between 0 and one.

Statistical analysis

Data from the quantification of Ni and Cr in sus scrofa skin were analyzed using the statistics software GraphPad Prism 6 (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, United states of america). A two-way ANOVA with Tukeys multiple comparison test was carried out to decide significant differences between the unlike groups. For both Ni and Cr ANOVA analyses degrees of freedom were two and iii for columns and rows, respectively. The F ratios for the different treatments were 60.82 for Ni and 100.one for Cr.

Availability of data and materials

The XRF data sets and fitted maps generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the data damsel repository [35]. All other datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Co:

-

Cobalt

- Cr:

-

Chromium

- Cu:

-

Copper

- Iron:

-

Iron

- Hg:

-

Mercury

- ICP:

-

Inductively coupled plasma

- LOD:

-

Limit of detection

- LOQ:

-

Limit of quantification

- MALDI-MS:

-

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry

- Ni:

-

Nickel

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- TiO2 :

-

Titanium dioxide

- XANES:

-

X-ray assimilation near-edge structure

- XRF:

-

Ten-ray fluorescence

References

-

Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler One thousand, Bäumler W. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparing to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226(ii):138–47.

-

Serup J, Sepehri Thou, Hutton Carlsen Chiliad. Nomenclature of tattoo complications in a infirmary fabric of 493 adverse events. Dermatology. 2016;232:668–78.

-

Kluger N. Epidemiology of tattoos in industrialized countries. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:6–xx.

-

Bicca JF, Duquia RP, de Avelar Breunig J, de Souza PR, de Almeida HL Jr. Tattoos on 18-yr-old male adolescents - characteristics and associated factors. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6):925–8.

-

Sowden J, Byrne J, Smith A, Hiley C, Suarez Five, Wagner B, et al. Ruby tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576–89.

-

Rorsman H, Brehmer-Andersson Eastward, Dahlquist I, Ehinger B, Jacobsson S, Linell F, et al. Tattoo granuloma and uveitis. Lancet. 1969;295(7610):27–8.

-

Morales-Callaghan AM Jr, Aguilar-Bernier Chiliad Jr, Martinez-Garcia G, Miranda-Romero A. Sarcoid granuloma on blackness tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 Suppl):S71–3.

-

Hering H, Sung AY, Roder N, Hutzler C, Berlien HP, Laux P, et al. Laser irradiation of organic tattoo pigments releases carcinogens with 3,3′-dichlorobenzidine inducing Dna strand breaks in human skin cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(12):2687–90.

-

Forte One thousand, Petrucci F, Cristaudo A, Bocca B. Market survey on toxic metals contained in tattoo inks. Sci Full Environ. 2009;407(23):5997–6002.

-

Serup J, Bäumler W. Diagnosis and therapy of tattoo complications. With atlas of illustrative cases. Basel: Karger; 2017.

-

Engel East, Vasold R, Santarelli F, Maisch T, Gopee NV, Howard PC, et al. Tattooing of peel results in transportation and light-induced decomposition of tattoo pigments - a commencement quantification in vivo using a mouse model. Exp Dermatol. 2010;nineteen(ane):54–60.

-

Sepehri M, Sejersen T, Qvortrup Yard, Lerche CM, Serup J. Tattoo pigments are observed in the Kupffer cells of the liver indicating claret-borne distribution of tattoo ink. Dermatology. 2017;233(1):86–93.

-

Schreiver I, Hesse B, Seim C, Castillo-Michel H, Villanova J, Laux P, et al. Synchrotron-based nano-XRF mapping and micro-FTIR microscopy enable to look into the fate and furnishings of tattoo pigments in human skin. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11395.

-

Høgsberg T, Loeschner M, Löf D, Serup J. Tattoo inks in general usage comprise nanoparticles. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(vi):1210–viii.

-

Bocca B, Sabbioni E, Mičetić I, Alimonti A, Petrucci F. Size and metal composition characterization of nano- and microparticles in tattoo inks by a combination of belittling techniques. J Anal At Spectrom. 2017;32(3):616–28.

-

Zhao F, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Chang X, Chen C, Zhao Y. Cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, and cytotoxicity of nanomaterials. Minor. 2011;seven(10):1322–37.

-

Cho M, Cho WS, Choi Thousand, Kim SJ, Han BS, Kim SH, et al. The impact of size on tissue distribution and emptying by single intravenous injection of silica nanoparticles. Toxicol Lett. 2009;189(3):177–83.

-

Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, Tomlinson MJ, Gavrilovic J, Black J, Peoc'h Thousand. Broadcasting of habiliment particles to the liver, spleen, and abdominal lymph nodes of patients with hip or knee replacement. JBJS. 2000;82(iv):457–77.

-

Krischak GD, Gebhard F, Mohr W, Krivan V, Ignatius A, Beck A, et al. Difference in metallic vesture distribution released from commercially pure titanium compared with stainless steel plates. Curvation Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124(ii):104–13.

-

Serup J, Hutton Carlsen Yard. Patch test report of ninety patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(due south) are generated in the pare through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71(5):255–63.

-

Hostynek JJ. Sensitization to nickel: etiology, epidemiology, immune reactions, prevention, and therapy. Rev Environ Health. 2006;21(4):253–80.

-

Slauch JM. How does the oxidative burst of macrophages kill bacteria? Still an open question. Mol Microbiol. 2011;fourscore(3):580–3.

-

Goodman SB. Wear particles, periprosthetic osteolysis and the immune organisation. Biomaterials. 2007;28(34):5044–8.

-

Emmett EA, Risby Thursday, Jiang L, Ng SK, Feinman Southward. Allergic contact dermatitis to nickel: bioavailability from consumer products and provocation threshold. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;nineteen:314–22.

-

Herting Chiliad, Odnevall Wallinder I, Leygraf C. Metallic release from various grades of stainless steel exposed to synthetic body fluids. Corros Sci. 2007;49(1):103–11.

-

Thomas P, Braathen LR, Dorig M, Aubock J, Nestle F, Werfel T, et al. Increased metal allergy in patients with failed metal-on-metallic hip arthroplasty and peri-implant T-lymphocytic inflammation. Allergy. 2009;64(viii):1157–65.

-

Hallib NJ, Jacobs JJ. Biologic effects of implant droppings. Balderdash NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2009;67(2):182–8.

-

De Cuyper C, Lodewick E, Schreiver I, Hesse B, Seim C, Castillo-Michel H, et al. Are metals involved in tattoo-related hypersensitivity reactions? A case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77(6):397–405.

-

Cobb HK, Shinohara MM, Huss JT, Welch MP, Gardner JM. Systemic contact dermatitis to a surgical implant presenting equally red decorative tattoo reaction. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3(four):348–l.

-

Perez-Gonzalez K, Ridge CD, Weisz A. Identification and quantification of the decarboxylated analogue of pigments red 57 and 57:1 in the color additives D&C red no. six, D&C red no. 7, and their lakes, using a chelating agent and UHPLC. Food Addit Contam Office A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2019;36(2):212–24.

-

Cotte Thousand, Pouyet Due east, Salomé 1000, Rivard C, De Nolf Westward, Castillo-Michel H, et al. The ID21 Ten-ray and infrared microscopy beamline at the ESRF: status and recent applications to artistic materials. J Anal At Spectrom. 2017;32(3):477–93.

-

Martinez-Criado G, Villanova J, Tucoulou R, Salomon D, Suuronen JP, Laboure S, et al. ID16B: a hard 10-ray nanoprobe beamline at the ESRF for nano-analysis. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2016;23(Pt 1):344–52.

-

Ravel B, Newville One thousand. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for Ten-ray assimilation spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2005;12:537–41.

-

Solé VA, Papillon E, Cotte G, Walter P, Susini J. A multiplatform code for the analysis of free energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectra. Spectrochim Acta Part B. 2007;62(1):63–viii.

-

Schreiver I, Hesse B, Seim C, Castillo-Michel H, Villanova J, Lagrange A, et al. Data from: distribution of nickel and chromium containing particles from tattoo needle wear in humans and its possible impact on allergic reactions. Dryad Digital Repository. 2019. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5qv3884.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros give thanks Deborah Stier, Nils Dommershausen, and Eric Riemer for their technical help with the SEM, MALDI-MS and ICP-MS analyses, respectively. Nosotros as well give thanks Dr. Rita Dubelloy for providing the peel specimen of the investigated tattoo allergy patient.

Funding

This piece of work was supported by the intramural research project (SFP #1322–604) at the German language Federal Institute for Take a chance Assessment (BfR). The authors would similar to give thanks the ESRF (The European Synchrotron) for allocated beamtimes on ID21 and ID16B for each of the experiments MD974 and MD1065.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

IS and BH designed and supervised the study. IS and BH planned the experiments. BH, HC-M, IS and CS performed the experiments at ID21. BH, IS, CS, JV and ALA performed experiments at ID16B. BH, IS, CS and HC-One thousand performed information analysis and the estimation of belittling XRF data. IS analyzed the samples by means of MALDI-MS. ND and IS carried out ICP-MS assay. IS, BH, HC-M and CS critically reviewed the data and drafted the manuscript. CS and LA analyzed the samples with the table top XRF. CS graphically designed the figures. RP and CD selected and provided human being specimens suitable for these experiments. ALU, MC and RT analyzed the overall results and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the terminal manuscript.

Respective author

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

The experiments were performed according to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Skin and lymph node samples were taken postmortem at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich (courtroom-ordered autopsies with no additional cosmetic impairment to the skin). The shave biopsy of the allergic patient was taken upon informed consent due to medical indication.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Additional Methods. Figure S1. Nano-10-ray fluorescence (XRF) maps of four peel and three lymph node samples analyzed at ID16B. Figure S2. Nano-X-ray fluorescence (XRF) maps of selected inks analyzed at ID16B. Figure S3. Adding of Ni and Cr contamination in sus scrofa skin and inks. Effigy S4. T-jail cell infiltration in tattoo allergy sample. Table S1. Titanium XANES spectra of eight human pare and six lymph node samples every bit well equally a skin allergy biopsy were fitted to pure anatase and rutile spectra of known standards. Table S2. MALDI-MS analysis of organic pigments in skin and lymph node samples. No pigments were found in the control samples. Table S3. Cr M-border micro-XANES spectra of human skin and lymph node samples were fitted to spectra of known Cr standards. Tabular array S4. Ni K-edge nano-XANES spectra of human skin and lymph node samples were fitted to known Ni standards. Tabular array S5. ICP-MS assay of elements in peel and lymph node samples. Increased values compared to pare or lymph node (LN) command samples are marked in bold. Table S6. Tabular array-height 10-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis of microtome blades used for sample preparation and commercial tattoo needles. Tattoo needles analyzed derived from vi dissimilar brands. Data are displayed as mean and standard deviation of north = two measurements. (DOCX 3000 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided yous give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nil/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this commodity

Schreiver, I., Hesse, B., Seim, C. et al. Distribution of nickel and chromium containing particles from tattoo needle wear in humans and its possible impact on allergic reactions. Part Fibre Toxicol 16, 33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-019-0317-1

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12989-019-0317-1

Keywords

- Metallic clothing

- Nickel

- Tattoo

- Titanium dioxide

- Synchrotron

- XRF

- Allergy

What Colored Tattoo Inks Contain Nickel,

Source: https://particleandfibretoxicology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12989-019-0317-1

Posted by: brownforsoust77.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Colored Tattoo Inks Contain Nickel"

Post a Comment